I was seven years old when I started learning to read, which is typical of the Steiner alternative school I attended. My own daughter attends a standard English school and started at age four, as is the case with most British schools.

Watching her memorize letters and speak words, at an age when my idea of education was to climb trees and jump in puddles, I wondered how our different experiences shape us. Does she benefit from a crucial advance that will benefit her all her life? Or is she exposed to excessive amounts of potential stress and pressure, at a time when she should be enjoying her freedom? Or am I just worrying too much, and it doesn’t matter what age we start reading and writing?

An Ethiopian schoolboy generates electricity for his village

Cameroonian teacher arrested after viral beating video

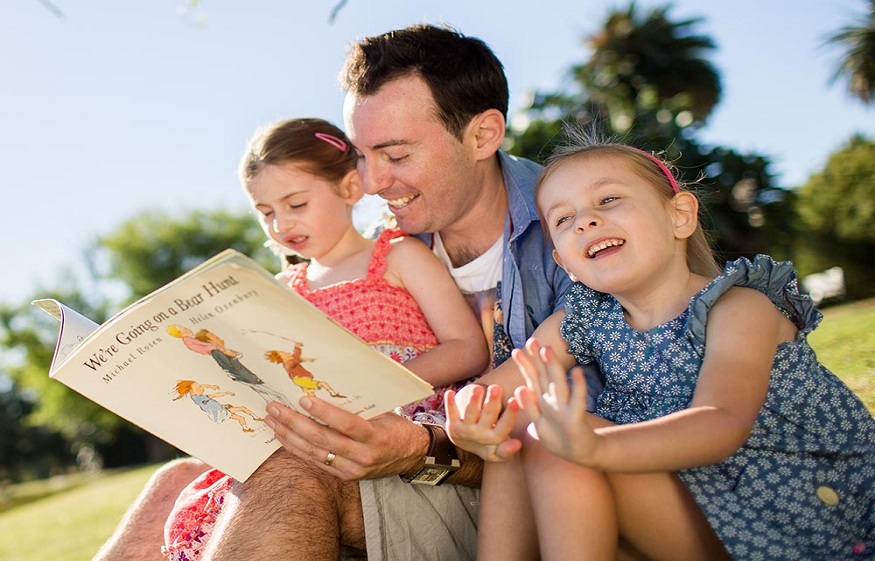

Babies already respond better to the language they were exposed to in their mother’s womb. There is evidence that the amount of talk we are told in childhood can have lasting effects on our future academic performance. Books are a particularly important aspect of this rich linguistic exposure, as written language often includes a broader and more nuanced and detailed vocabulary than everyday spoken language. This in turn can help children increase their range and depth of expression.

In many countries, formal education begins at age four. This can, however, result in a “race for education”, with parents trying to give their child early advantages in school through private tutoring and teaching, and some parents even paying for that four-year-olds benefit from additional tutoring. Comparing this to the more play-oriented early education that existed decades ago, there is a huge shift in policy, based on very different ideas of what our children need to progress. In the United States, this emergency is is accelerated with policy changes such as the 2001 “no child left behind” law, which encouraged standardized testing as a means of measuring educational performance and progress. In the UK, children are tested in the second year of school (5-6 years) to check that they are achieving the expected reading level. Critics of this kind of early testing warn of the risk of putting children off reading, while proponents say it helps identify those who need extra support. school (5-6 years old) to check that they are reaching the expected reading level. Critics of this kind of early testing warn of the risk of putting children off reading, while proponents say it helps identify those who need extra support. school (5-6 years old) to check that they are reaching the expected reading level. Critics of this kind of early testing warn of the risk of putting children off reading, while proponents say it helps identify those who need extra support.

Wearing the hijab does not mean that Muslim women are oppressed”

However, numerous studies show that the benefits of an excessive early school environment are minimal. A 2015 U.S. report says society’s expectations of the outcomes children should achieve in kindergarten have changed, leading to “inappropriate classroom practices” such as reduced learning through play.

The risk of “schooling”The way children learn and the quality of the environment are extremely important. “Teaching young children to read is one of the most important things primary education does. It’s fundamental for children to progress in life,” says primary education teacher Dominic Wyse at University College London, UK. With sociology professor Alice Bradbury, also at UCL, he has published research which shows that how we teach reading and writing really matters. In a report published in 2022, they claim that the accent put by the English school system on phonics – a method of matching the sound of a word or

I secretly tutored children of ISIS fighters

Part of the reason, Bradbury says, is that ‘early years schooling’ resulted in more formal learning at an early stage. But the tests used to assess this early learning don’t necessarily have much to do with the skills actually needed to read and appreciate books or other meaningful texts. For example, the tests may ask students to “pronounce” and spell nonsense words, to prevent them from just guessing or recognizing familiar words. As nonsense words do not constitute meaningful language, children may find the task difficult and confusing. Bradbury found that the pressure to learn these decoding skills – and pass reading tests – also means that some three-year-olds are already being exposed to phonics. “It ultimately doesn’t make sense, you end up memorizing rather than understanding the context,” says Bradbury. She also worries that the books used aren’t particularly appealing.